Map showing the locations of Alaska Territorial Guard units (with membership counts), major military bases, and evacuated Aleutian villages. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Jay Griffin, CC BY-SA 3.0

A living legacy of the Cold War is the prevalent concern among the American political elite that Russia and China could form an alliance, which may potentially pose a threat to the United States. Whatever the party is in power, Republicans or Democrats, this threat continues to be taken seriously. In practice, this is just “a bad dream” for American politicians and military officers through generations. The Congressional Research Service has recently observed that current terrestrial and space-based sensor architectures in the US are inadequate for detecting and tracking nuclear-tipped hypersonic weapons developed by Russia and China. In pursuit of the principle of “peace through strength”, the executive order asserted that “the United States will guarantee its secure second-strike capability”.

It is noteworthy that all American missile defence systems, such as THAAD, Patriot, and Aegis Ashore, do not possess nuclear warheads and are categorised as “kinetic kill” weapons. The Trump administration’s 2025 Iron Dome Act programme, which draws on the foundations laid by Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defence Initiative, is set to initiate the production of new ballistic medium- and short-range missiles, including hypersonic ones. While the programme has raised many questions, actively circulating claims about the special threat from hypersonic weapons may be nothing more than Department of Defence hype, as cited by Scientific American, since their initial launch and detection would not be much different from current intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Alaskan Strategic Role Outed Long Ago

Since the 1950s, Alaska has played a pivotal role in the US missile defence—and that responsibility remains just as vital as ever. Referring the Russia-China joint patrol in the Bering Sea as “incursions” in Alaska’s Air Defence Identification Zone and Exclusive Economic Zone, Senator Dan Sullivan of Alaska stated:

This is the northern border, and our adversaries are all over it. In my view, what we need is a lot more infrastructure, a lot more military, a lot more missile defence, a lot more unleashing Alaska’s critical minerals, oil and gas.

Alaska is home to eight major military installations, each of which provides support to various branches of the US Armed Forces. These include Eielson Air Force Base, Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER), Clear Space Force Station, Fort Wainwright, Fort Greely, Coast Guard Base Kodiak, Marine Safety Unit Valdez, and USCG Sector Juneau. The US 2025 National Defence Authorisation Act, thanks to the efforts of Senator Sullivan, allocated 723.3 million dollars for construction in Alaska bases, with the majority of these funds allocated to Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, the largest military installation in the district, out of the total 895 billion dollars investment in military infrastructure across the country.

The turning points of Alaskan military build-up are as follows:

- Between 1940 and 1943, a network of airfields was established in Alaska. Ladd Airfield, located at Fort Wainwright, Elmendorf Field, and Ford Morrow Airfield (Kodiak), were the earliest combat airfields. The other Alaskan combat airfields were constructed along the Aleutian Islands between 1942 and 1943.

- Another important thing is that during WWII and Japan’s invasion of coastal Alaska, Alaska Native nations worked with the United States in a new way, especially through the ATG (the Alaska Territorial Guard). Using the ATG to organise themselves, Alaska Natives protected more than 5,200 miles of the Alaskan coastline. The ATG operated until 1947.

- The Eisenhower Administration (1953-1961) took further action by placing missile defence on Alaskan soil. The earliest of these was the DEWline system, which was launched in 1954. The BMEWS system, which has been in operation since 1961, is considered to be of greater significance. It is based 75 miles south of Fairbanks at Clear Space Force Station.

- In the early 2000s, the US set up its Ground-Based Midcourse Defence (GMD) system at Fort Greely. This system represented a substantial advancement in ballistic missile defence technology in comparison with previous installations, complete with command and control, interceptors, sensors, electromagnetic pulse resistant infrastructure, power, facilities, and dedicated logistics. At present, the GMD system is integrated with other air defence networks, including the Aegis missile defense system on US Navy ships and the land-based Patriot and THAAD missile batteries.

Again, none of these missile defence systems are equipped with nuclear warheads. None of ground-, air- or ship-based ballistic missiles as well as hypersonic missiles are in service with the US Armed Forces, but are in plans to be produced (with no certain time).

Some Consequences Forgotten

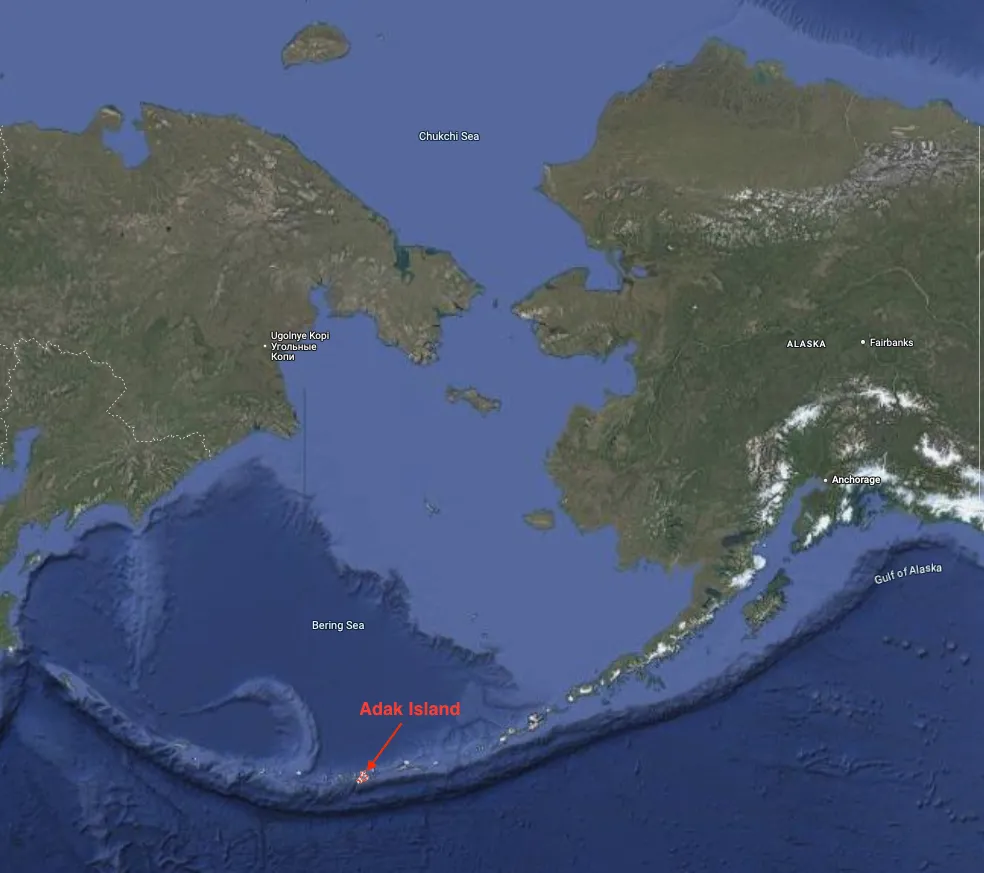

As well as running military bases and radar sites, the military plans to rebuild particular military installations that were left behind after the end of the Cold War. In April, for instance, the top commander in the Pacific, Adm. Samuel Paparo, joined other military officials in calling for a base on Adak Island to be rebuilt. Adak Island is a tiny, rocky outpost in Alaska’s Aleutian Island chain. The island, which sits halfway between mainland Alaska and Russia, would give the US “an opportunity to gain time and distance on any force capability that’s looking to penetrate,” Paparo said at a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing.

Location of Adak island on the map. Author. Created with Google maps.

The northern half of Adak Island has been used by the US military since the 1940s. With about 90,000 soldiers mobilised to the Aleutians, Adak was used by the Army Air Corps for defensive operations against the Japanese during the battles at Attu and Kiska islands. After World War II, the military presence on the island fluctuated, but generally did not exceed 6,000 personnel. The base and the island were later renamed Davis Air Force Base. In 1950, the Air Force withdrew and the Navy took control over the US military installations. In less than a decade, a federal land grant removed more than 79,000 acres of northern Adak Island from Navy use.

The military’s mission on Adak officially ended in 1997. Since then, the Navy’s presence has included environmental restoration and cleanup after military dumps and chemical spills contaminated the island’s groundwater, surface water, sediments, and soil.

Adak Naval Air Station was included in Superfund National Priorities List due to hazardous substances like petroleum, chlorinated solvents, batteries, transformer oils, pesticides and solvents that were disposed of across the island. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the island also has roughly 70,000 unexploded ordinances which has led to restrictions in some areas.

The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), is the primary law governing cleanup of hazardous waste sites in the United States. It imposes on polluting parties a non-discretionary duty to select remedial actions that protect human health and the environment.

Furthermore, Alaska’s state cleanup standards determine the level of contaminants permissible notwithstanding that federal agencies perform the cleanup: CERCLA provides that contaminated sites must meet either federal standards or any more stringent state standards relevant and appropriate to a site’s circumstances.

However, not all contaminated areas resulting from military use bother federal and state authorities. To give an example, the US Environmental Protection Agency declined the petition by local tribes on the Sivuqaq (a traditional name of St. Lawrence Island) to put the Gambell and Northeast Cape formerly used defense sites (FUDS) on the Superfund List of the most urgent sites that need remediation.

A Sad Story of Friendship between the US Military and the Locals

There are over 700 abandoned defence sites in Alaska that operated from World War II to the Cold War— Gambell and Northeast Cape are the more infamous due to its extensive pollution.

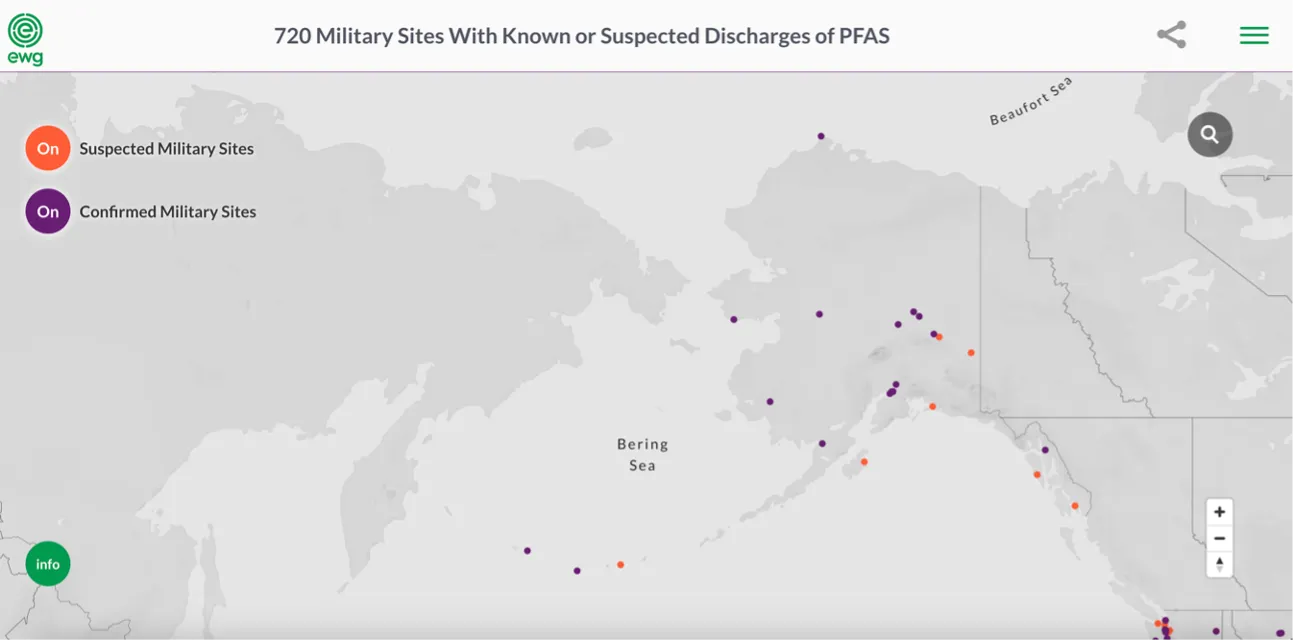

PFAS Contamination in Alaska. Source: Environmental Working Group

In June 1942, Japan’s invasion of the Aleutians in Alaska prompted the US military to activate the Alaska territorial guard, an Army reserve made up of volunteers who wanted to help protect the US So many of the volunteers were from Alaska’s Indigenous peoples—Aleut, Inupiak, Yupik, Tlingit, and many others—that the guard was nicknamed the “Eskimo Scouts”.

Alaska natives defended their territory 83 years ago. Retired Sgt. 1st Class Sam Jackson, who served in the Alaska Territorial Guard during World War II, poses for a photo inside his home in Kwethluk, Alaska, September 23, 2017. Source: US Department of Defence

According to Alaska Beacon’s investigation, following World War II ended and the Reserve Force ceased operations in 1947, the US approached the indigenous Yupik people of Alaska with another request:

Could the Air Force set up “listening posts” on the Sivuqaq to help gather the intelligence needed to win the Cold War?

Viola Waghiyi, who is Yupik from Sivuqaq, said the answer was a resounding yes.

Our grandfathers and fathers volunteered for the Alaska territorial guard, she said. We were very patriotic.

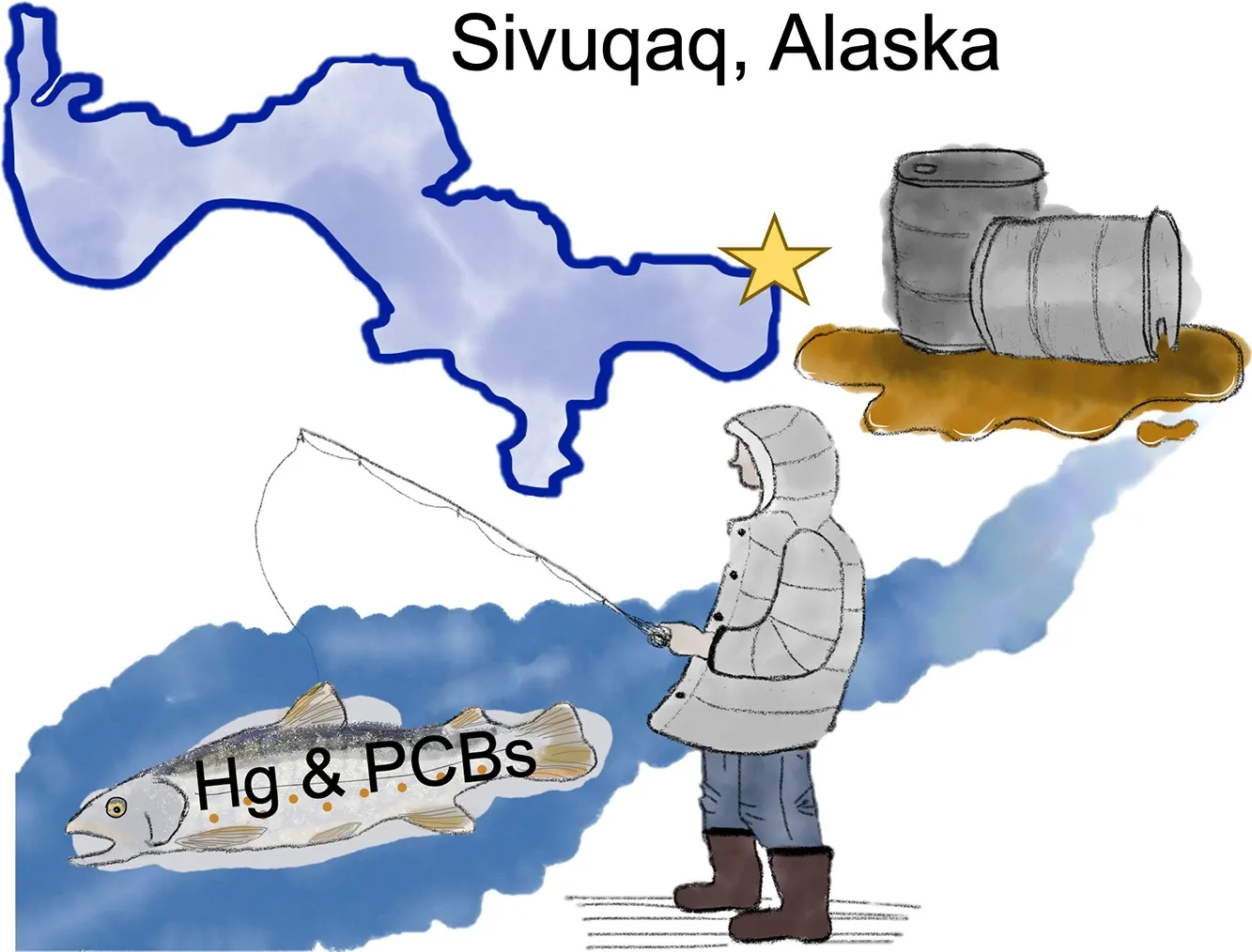

Elevated mercury and PCB concentrations in Dolly Varden (Salvelinus malma) collected near a formerly used defence site on Sivuqaq, Alaska. Source: Science Direct

In 1951 an agreement was signed between the Savoonga Council and the US Air Force. It restricted the use of the area and required the USAF to protect the purity of the Indigenous land. In particular, the USAF agreed not to dump refuse in the streams or along the beach near the proposed military area.

But that trust was betrayed, Waghiyi said.

Not only did the USAF violate this agreement during the period of active military use, but they also failed to clean up their waste in the form of abandoned drums and toxic chemicals, which contaminated large areas of traditional lands, in violation of the agreement.

The US military eventually abandoned its air force and army bases, leaving the land contaminated with toxic chemicals such as fuel, mercury and polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, known as “forever chemicals” because they persist in the environment for so long. Most of the contamination came from spilled and leaking fuel from storage tanks and pipes, both above and below ground. Other chemical waste came from electrical transformers, discarded metals and 55-gallon drums.

On March 12, native village of Gambell and native village of Savoonga, filed a complaint with the UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights, a Special Procedure of the UN Human Rights Council, concerning toxic military contamination on Sivuqaq Island. The Sivuqaq tribal leaders demanded that the US government be held accountable for long-term multi-generational harms and called on the US Army Corps of Engineers to re-open its record of decision related to the cleanup of the former military sites at Gambell and Northeast Cape, Alaska.

Our community-based research in partnership with the Tribes of Sivuqaq has demonstrated the long-term and intergenerational environmental and health harms perpetrated by the US military, said Pamela Miller, Executive Director and Senior Scientist with Alaska Community Action on Toxics (ACAT).

Military Contamination Continues to Affect Local Food Webs

Here some extracts from a filed complaint are provided, highlighting research on the impact of military contamination on local food webs.

Subsequent research has focused on evidence of contamination of local foods—and the ecosystems on which they depend—that are part of the Yupik’s traditional subsistence diet:

- A 2011 paper investigated PCBs in blubber and rendered oils from bowhead whale, walrus, and seals. These marine mammals are major contributors to the Yupik’s subsistence diet.

- A study published in 2017 investigated contamination of stickleback, a sentinel fish, taken from Troutman Lake near Gambell, by polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

- A 2020 paper investigated semi-volatile organic chemical contamination in stickleback collected from Troutman Lake, near Gambell. Researchers concluded that “chemical patterns … in comparison with SVOC concentrations in stickleback from other parts of the island suggest strong local sources of PCBs, PBDEs, and PFAS.”

- A study published in 2022 tested Dolly Varden trout, an important subsistence food fish, taken from the Suqi River over a three-year period, downstream from the NEC FUDS. It found that, “all fish sampled near the FUD site exceeded the EPA’s PCB guidelines for cancer risk for unrestricted human consumption.”

- The same study also found that “89% of fish collected from near the FUD site had Hg [mercury] concentrations that exceeded the US EPA’s unlimited Hg-contaminated fish consumption screening level for subsistence fishers.”

- A study published in 2023 reported that “PCB concentrations in Troutman Lake stickleback exceeded (by 3.8-fold) the EPA’s guideline for unlimited fish consumption.”

The compilers of the document point out that despite a number of scientifically validated research have been conducted, the US Army Corps of Engineers has denied it, and continues to deny, that further characterisation and remediation of the Gambell and Northeast Cape FUDS is required to protect the health of the Yupik people and their ecosystem.

The military end cannot justify the means of polluting drinking water, air and soil with chemicals.

The Arctic Century